Round The World and other travels

A frequent flyer's collection of trip diaries

This is: African Contrasts 2015

Carved out of the earth itself: the churches of Lalibela

We got up at the perfectly hideous hour of 0430

(or as Bruce called it, "OMG o'clock"

![]() ) and made sure we were ready to catch the 0600 bus to the airport,

after checking out of the Hilton and placing our main luggage in

storage to await our return the following day. Travelling only with

light carry-on bags, we remained on the shuttle after the first stop

and were driven round to the domestic terminal. Following a

two-sector journey on a Dash-8 turboprop that called briefly at

Gondar, we arrived at Lalibela in

bright, sunny conditions; it felt as though quite a lot had already

been accomplished and yet it had just gone 9:30 in the morning. A

further shuttle took us from this small airport, through undulating

and sometimes hilly, wild-looking countryside, to the town of

Lalibela and our latest lodgings.

) and made sure we were ready to catch the 0600 bus to the airport,

after checking out of the Hilton and placing our main luggage in

storage to await our return the following day. Travelling only with

light carry-on bags, we remained on the shuttle after the first stop

and were driven round to the domestic terminal. Following a

two-sector journey on a Dash-8 turboprop that called briefly at

Gondar, we arrived at Lalibela in

bright, sunny conditions; it felt as though quite a lot had already

been accomplished and yet it had just gone 9:30 in the morning. A

further shuttle took us from this small airport, through undulating

and sometimes hilly, wild-looking countryside, to the town of

Lalibela and our latest lodgings.

The Maribela Hotel created favourable first impressions, being fairly new and nicely decorated. Our room was available on arrival, and we quickly appreciated the fine view from the balcony. Getting to know our latest quarters provided something of a diversion, as did our invitation to join an Ethiopian coffee ceremony, laid on as a gesture of welcome. In accordance with tradition, the ceremony was performed by a woman, and the freshly brewed beverage was served on a tray covered in aromatic grasses. Coffee is regarded as having spiritual significance in Ethiopian culture and again as required by tradition, the ceremony was accompanied by the burning of incense. As the sweet smoke wafted upwards from the little censer, Bruce commented that it transported him back to his schooldays in Cheltenham, where elaborate high-church ritual had been a memorable feature of his formative years. This indeed was elevenses with a difference.

|

|

|

LEFT: Arrival in Lalibela and subsequent coffee ceremony. Two of the photos show depictions of rock-hewn churches. |

|

|

|

|

RIGHT: Lalibela street scene in the early part of the afternoon |

After having a light lunch at the hotel and as the afternoon opening time of 2pm approached for our objective, we were ready to dedicate the next few hours to what had drawn us to this remote spot in the first place: an astonishing cluster of eleven 900-year-old churches, not built in the conventional manner from the ground up, but hewn out of solid rock. First, though, a little bit of background wouldn't go amiss:

Ethiopia is a majority-Christian country. The Christian tradition dates all the way back to the first century AD, making Ethiopia unique in this respect among the sub-Saharan countries of Africa. The largest denomination is the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, part of the Oriental Orthodox Church (which should not be confused with the similar-sounding Eastern Orthodox Church). Lalibela is considered to be the second-holiest city in Ethiopia, after Aksum, and is best known for the rock-cut churches that we had come to see. The layout and naming of these churches is thought to be a symbolic representation of Jerusalem. The town itself, originally called Roha, is named after Gebre Mesqel Lalibela, who ruled Ethiopia in the late 12th century and is a saint in the Ethiopian church. Most of the monolithic churches are thought to have been built during his reign, and as a group they have formed a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1978.

After paying the hefty entrance fee of USD50 per person, which included the services of a guide, we explored some of the best preserved examples, situated near a traditional village featuring circular-shaped dwellings. The rough terrain and 8,500ft elevation made for relatively arduous walking conditions, but the objective justified the physical effort. The first two churches visited were the fairly small House of Mary and the much larger House of the Saviour. Temporary protective canopies had been erected over these churches in an effort to slow down a recently accelerated rate of deterioration.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE and RIGHT: House of Mary and House of the Saviour | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: Traditional Ethiopian circular houses, situated close to the rock-hewn churches |

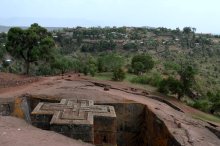

Although we had neither the time nor the energy to visit all the churches, we made sure that our visit included the youngest, best preserved and most remarkable of the eleven: the Church of St George, with its instantly recognisable symmetrical, cruciform layout. Often suggested as a candidate for the title Eighth Wonder of the World, this church was not carved into a vertical wall of rock but was created by working downwards from ground level, so that the building that emerged stood in a man-made pit. It's interesting to take a moment to think that process through. The normal method of erecting a building, following preparation of the foundations, is to pile the stones or bricks on top of each other until the desired shape is created. (Of course there's rather more to it than that, if you want to ensure that the structure doesn't collapse through inability to support its own weight, but that's the essence of the process.) If you make a mistake when adding a component, you can always knock the offending piece back out and replace it correctly before carrying on.

|

LEFT: An Ethiopian Orthodox priest in attendance at the Church of St George |

With St George's, the process was to dig down into a single, massive lump of solid rock. As each piece of rock was removed, the builders were not directly adding to the church itself but rather creating the empty space around it, starting at the top and working downwards. The church that we see today is what was left of the original rock after the pit had been excavated and the interior of the structure hollowed out. If one careless swing of the pick had removed a piece of rock that ought to have been left in place, any attempt to add that piece back would have destroyed the monolithic nature of the structure. In many ways it seems similar to what a sculptor does to transform a solid lump of stone into a statue, only on a very much larger scale.

Am I alone in thinking that we would probably struggle to achieve such an awe-inspiring feat today, even with the benefit of modern power tools and computer-aided design? For such an unusual construction method to have been successfully employed in the thirteenth century is, to me at least, almost beyond comprehension.

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: Views of the Church of St George from various perspectives, from above surface level to the floor of the excavated pit | |||

| BELOW: House of Emmanuel, the final church visited. Also shown are further examples of traditional circular houses and an indication of the type of terrain being traversed. | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

After St George's, we visited one more of these remarkable structures - the House of Emmanuel - before the combination of altitude, heat and steep paths began to take its toll, and we knew it was time to call it a day and return to base for a well-earned rest.

While I definitely felt the benefit of a couple of hours of relaxation, Bruce was less fortunate and managed to develop an upset stomach. As a result, we abandoned the planned visit to a nearby restaurant and instead I had a fairly simple evening meal in the attractive surroundings of the hotel's own dining room.