Round The World and other travels

A frequent flyer's collection of trip diaries

This is: A Taste of the Deep South (2013)

Top city

Today was given over to exploring the genteel charms of Charleston, originally Charles Towne in honour of Charles II of England. The city’s nickname, The Holy City, derives from the abundance of church steeples in a low-rise skyline, rather than any excess of piety. Unlike many colonial cities in America, Charleston was a business venture from the beginning and has always been known as a city of hard drinkers, serious foodies and astute traders, cloaked in a charm that many have mistaken as a weakness, only to find out that they had met a formidable foe.

Charleston made news in 2011 when it unseated San Francisco for the first time ever in the annual Condé Nast Traveler Reader’s Choice Awards, as Top US City - quite a coup for this smallish, rather old-fashioned and fairly conservative city in the Deep South. Perhaps the most revealing award, however, is its perennial ranking atop the late Marjabelle Young Stewart annual list for Most Mannerly City in America. This city takes its quality of life and gentility so seriously that it founded the concept of a Livability Court - since copied elsewhere in South Carolina - which meets regularly to enforce local civic harmony ordinances.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: Murray Blvd., The Battery and the Louis de Saussure House | ||

After breakfast in the Courtyard restaurant, we set off around 0900 and drove from the hotel to the southern tip of the peninsula, where we found free parking along the Murray Boulevard. We began with a short wander through the peaceful White Point Gardens (a.k.a. The Battery), named for the sun-bleached oyster shells that dominated the land about 400 years ago when the first European settlers gave it its original name, Oyster Point. As we left the park to the southeast where South Battery Street curves north to become East Battery Street, we saw a three-floor private residence, the Louis de Saussure House, best known in Charleston history for hosting rowdy, celebratory crowds on the roof to watch the 34-hour shelling of Fort Sumter in 1861.

|

| ABOVE: Edmonston-Alston House |

As we continued up East Battery Street, we saw the 1825 Edmonston-Alston House (21 E. Battery) on our left, a curious mix of its original Federal style and newer Greek Revival elements, notably the parapet, balcony and piazza added by the second owner. It was from here that General Beauregard watched the attack on Fort Sumter. Continuing north, East Battery Street became East Bay Street, and the section between Tradd and Elliott Streets (79-107 E. Bay) is said to be one of the most photographed sights in the country: colourful Rainbow Row. The bright, historically accurate colours are one of the many vestiges of Charleston’s Caribbean heritage, a legacy of English settlers from the colony of Barbados, who were among the city’s first residents.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| ABOVE: East Battery and East Bay, including Rainbow Row | ||||

|

LEFT: A couple of rather more quirky views of Charleston life, taken during this early part of the day's proceedings |

|

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon | |

A couple of blocks up East Bay Street was the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon (1771). Known as one of the most historically significant buildings in the United States along with Independence Hall in Philadelphia and Faneuil Hall in Boston, this was actually the old Royal Exchange and Custom House, with the cellar serving as the British prison. Three of the four Charleston signers of the Declaration of Independence did time downstairs for sedition against the Crown. Set in such an important historical building, the museum was a curious mixture of genuine artefacts alongside some utter rubbish, presumably intended to fill otherwise empty space. We gave the kitschy, animatronic figures in the dungeon a wide berth, though this may just have been so awful as to become interesting on that basis. Overall, a classic case study to support the assertion that 'less is more'!

Upon exiting the museum,

we went east on Exchange Street to Waterfront Park to see the

Pineapple Fountain and hopefully to admire the views of Charleston Harbor and the Cooper River.

We certainly achieved the first of those objectives, and didn't know

whether to giggle or shake our heads in dismay at the official sign

warning unwary visitors such as ourselves that there was no

lifeguard on duty. Erm, it's a fountain, folks!

Upon exiting the museum,

we went east on Exchange Street to Waterfront Park to see the

Pineapple Fountain and hopefully to admire the views of Charleston Harbor and the Cooper River.

We certainly achieved the first of those objectives, and didn't know

whether to giggle or shake our heads in dismay at the official sign

warning unwary visitors such as ourselves that there was no

lifeguard on duty. Erm, it's a fountain, folks!

![]() The first heavy shower of the day broke at this point and saw us

making a hasty return to East Bay St to take refuge in the Bakehouse

coffee shop.

The first heavy shower of the day broke at this point and saw us

making a hasty return to East Bay St to take refuge in the Bakehouse

coffee shop.

After

a short break and with the weather improving a little, we headed

into the French Quarter. Unlike its counterpart in New Orleans,

this one is Protestant in origin and flavour, dating back to

the French Huguenots who fled here to escape religious persecution

at home. According to Bruce's guidebook, we were now entering the most evocative

and charming

part of the city, and our time here would be well spent merely wandering the narrow

streets.

After

a short break and with the weather improving a little, we headed

into the French Quarter. Unlike its counterpart in New Orleans,

this one is Protestant in origin and flavour, dating back to

the French Huguenots who fled here to escape religious persecution

at home. According to Bruce's guidebook, we were now entering the most evocative

and charming

part of the city, and our time here would be well spent merely wandering the narrow

streets.

Our first significant stop was at the Old Slave Mart Museum on Chalmers Street. Slave auctions were huge business in the South, and Charleston was no exception. They generally took place in public buildings, but in the 1850s that was stopped when city leaders discovered that visitors from European nations, all of which had banned slavery years before, were horrified by the practice. The auctions moved to private marts down by the Cooper River, out of the public eye. We went inside for a look around this sobering reminder of what once went on here.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: Continuing our walk towards the Dock Street Theatre | ||

Continuing west along Chalmers, we took a right at the next corner onto Church Street and walked up the block to Queen Street. On the corner of Church and Queen, we found the French Huguenot Church (1845) on our right, and the Dock Street Theatre (1835) on our left. The French Huguenot Church is home to one of the oldest congregations in town, and is the last remaining independent Huguenot Church in the USA.

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: French Huguenot Church | |

The original sanctuary was built on this site in 1687 and called Church of the Tides, in reference to the Cooper River that lapped at its property line. (In other words, everything east of us at this point, as far as the river, was there as a result of subsequent landfill.) It burned down in 1796, and again in 1800, and the present-day structure that we saw was completed in 1845. It has withstood both Union shelling and the great earthquake of 1886. If the building looked Dutch to us, it was because the French Huguenots spent a lot of time in Holland during their diaspora, and took with them many of the architectural traits of the time. The 1845 organ is a rare example of a tracker organ, so named for its ultra-fast linkage between the keys and the pipe valves.

The Dock Street Theatre was the first theatre built in the western hemisphere, but as with many of Charleston’s edifices, the 1736 original burned down, as did the 1754 and 1773 incarnations. The structure that we saw dated from 1809, with the façade added in 1835 to mark the theatre's centennial.

We continued northward

up Church Street, crossing Queen Street. Halfway up the next block

on our right was St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, the oldest

Anglican congregation in the South. The history of the church is

complicated. The first St. Philip’s was erected in 1680 on the

present site of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, but it was destroyed

by the hurricane of 1710. The new (and current) location was

selected on Church Street, but that building was destroyed during

construction by another hurricane. The local Indians attacked and

pillaged the next building in 1721, and after a lengthy delay a new

church was completed, only to be burned to the ground in the fire of

1835. The present-day building was the replacement for that

structure, but it was in turn heavily damaged by Hurricane Hugo in 1989.

Does

somebody up there have an issue with Anglicans, we wondered?!

![]()

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE, LEFT and RIGHT: St Philip's Episcopal Church |

We continued our walk up Church Street to the end of the block and turned left onto Cumberland Street. A few doors down on the left was the Old Powder Magazine (1713). Small but significant, this was the oldest public building in South Carolina, and the only one remaining from the days of the English Lords Proprietors, who ruled the original settlement. As the name indicates, this is where they stored the gunpowder during the Revolution, and the magazine was cleverly designed to implode rather than explode in the event of a direct hit. Next door was the privately owned Trott’s Cottage (1709), which was the first brick-built dwelling in Charleston.

|

|

|

ABOVE and LEFT: Circular Congregational Church |

We turned left onto Meeting Street and quickly found the Circular Congregational Church (1891). Originally founded in 1681 as the White Meeting House for which Meeting Street is named, it hosted services for Congregationalists, Huguenots and Presbyterians, hence taking the nickname Church of the Dissenters, which was the common term at the time for anyone not aligned with the Anglican Church. The 1886 earthquake destroyed much of the original building, and the 1891 edifice is what survives today. It differs from other Charleston churches in having no steeple, instead staying low to the ground in an almost medieval fashion.

|

|

ABOVE:

Bus shelter with a view ... and more importantly, a roof! |

We continued down Meeting Street towards the intersection known as Four Corners of Law, named for its confluence of federal law (represented by the US Post Office), state law (the state courthouse), municipal law (City Hall), and God’s law (St. Michael’s Episcopal Church.) At this point the heavens opened in spectacular fashion and we were forced to take refuge in a bus shelter opposite the courthouse. When the deluge abated, we were ready to take a closer look at St Michael's.

St. Michael’s is the oldest church in South Carolina, and as we heard earlier was originally the location of St. Philip’s. The designer of St. Michael’s is unknown, but the sanctuary is in the style of Sir Christopher Wren, so he was presumably from the motherland. Today's structure is basically the original from 1761, with the exception of a small addition to the southeast corner in 1883. The 186-foot steeple was painted black during the Revolution in a futile attempt to disguise it from British guns. It actually sank 8 inches during the great earthquake of 1886. The bells have made seven transatlantic voyages over the years. They were originally cast in London at the Whitechapel Foundry and shipped over in 1764, only to be taken back to England as a war prize during the Revolutionary War. Returned to the church after independence, they were severely damaged during the Civil War, so they were sent back to Whitechapel to be recast, and again returned to Charleston. Then Hurricane Hugo dealt them another blow in 1989 and they were once again shipped to London for recasting, making the final journey back to Charleston in 1993!

One of the most memorable aspects of our short visit was that it was accompanied by live organ music, which really filled the building's small interior.

|

|

|

|

LEFT: St Michael's Episcopal Church, in the aftermath of a spectacular downpour |

|

|

|

It was now high time that we were thinking of lunch, so we strolled

up Broad Street towards our planned stop at Gaulart & Maciclet's

Fast & French. In what had almost

become the established pattern for the trip, our plan was frustrated

by the place being full to overflowing. It was no disaster, however:

we found the excellent and popular King Street branch of Bull

Street Gourmet & Market just around the corner and had a lovely

lunch of nicely chilled Vichyssoise soup followed by duck club

sandwich, washed down with a very nice half-bottle of Californian

white wine. Absolutely delicious!

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| ABOVE: Broad, Legare and Archdale Streets, finishing in Charleston Market | |||

After lunch, realising that we had completed most of the planned sight-seeing and therefore having some additional time on our hands, we took a stroll further up Broad Street and along Legare and Archdale Streets in an attempt to loop back to Charleston Market. On the way, we saw more attractive houses and at least three additional places of worship, in the form of the Roman Catholic cathedral and the Unitarian and Lutheran churches.

I liked the market; it was a nice break from churches, slaves and war! Old-timers claim that its shabby charm has been lost in the latest renovation, and that it has been turned into an air-conditioned shopping mall. Frankly, I for one was grateful for the benefit of modern air-conditioning at this point and it still seemed possible to gain a sense of what the original market was like.

We emerged from the east side of the market onto Church Street, where we began our walk back towards the car by heading south, past the now familiar St Philip’s and French Huguenot Churches. Between Elliot Street and Tradd Street we came across some interesting addresses. First, at 94 Church Street, was the house where John C Calhoun drew up the papers for the infamous Nullification Act that eventually led to the South’s secession from the Union. Just down and across the street was Cabbage Row, at 89-91 Church Street, better known as 'Catfish Row' in Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess, itself based on the book Porgy by noted Charleston author DuBose Heyward, who lived a few doors down at 76 Church Street. Cabbage Row once housed 10 families of freed African-American slaves in tenement conditions, and still holds humble appeal despite obvious upgrades from years past.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT:

Old friends revisited ABOVE and RIGHT: The Porgy and Bess connection |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT and BELOW: And finally, back to the car |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE: From the sublime

to the ridiculous ... oh no, the pigs are back! |

|

Church Street eventually led us back to The Battery where we had parked in the morning. We needed to stock up with a few odds and ends before returning to base, so a quick diversion to the supermarket was in order and in the South, there's a good chance that'll mean a branch of Piggly Wiggly. No, seriously, there actually is a very large supermarket chain with that name and despite over 30 previous visits to the USA, I'd never knowingly run into it before - and I think I would have remembered if I had! It provided another reminder of the pig fixation that I had noticed quickly after arrival in the Deep South.

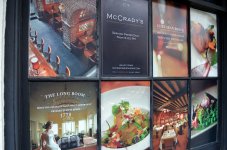

Finally returned to the Courtyard, we made arrangements for a taxi back into town for later, then took a well-earned opportunity to rest our weary feet. Before too long, it was time to freshen up and head off again for a blowout, farewell-to-Charleston dinner at McCrady's.

|

|

| ABOVE: And back to the sublime - our chosen dinner venue | |

It turned out to be an absolutely fabulous night out. I thought the venue was something of a masterpiece of physical design. We started off with cocktails in the most attractive bar. We then both decided to have the recommended four-course meal. I started with beef tartare and followed this with trout served with fresh local shrimp. I drank the recommended sparkling Chenin Blanc with these.

Next up was a generous portion of lamb, followed by the Chef's cheese selection. By this time we were sharing a half-bottle of Californian Syrah. This restaurant is very highly recommended (unless, that is, you're on a tight budget!) and the experience was a hugely enjoyable way to mark the end of our time in the Deep South.