Round The World and other travels

A frequent flyer's collection of trip diaries

This is: Bohemian Rhapsody (2014)

Prague, Old and New

We had planned another early start on Monday, but two differences were immediately obvious when I pulled back the curtain for a first look outside. For one thing, the streets below that had been near-deserted 24 hours earlier were now busy with people making their way to work. Our room overlooked a railway station that had scarcely seen an arrival or departure the previous day, at least during the times when we had been there to witness it. Now there were trains arriving every few minutes to disgorge further hordes of commuters. The other big difference was that the previous day's blue skies and sunshine had disappeared, so that I was now looking at a view that felt like a study in shades of grey. There was no point in bemoaning the change; it was, after all, the beginning of March.

New Town

|

LEFT: Grand Jerusalem Synagogue, also known by the name 'Jubilee' |

|

| RIGHT: The beautiful interior of the older part of Prague's main railway station |

Just as Sunday had been mainly dedicated to exploring the two city-centre quarters on the left bank of the Vltava, today's agenda focused exclusively on the right bank, consisting of the Old Town (Staré Město) and so-called New Town (Nové Město). The New Town actually dates from 1348 and is therefore a nice little demonstration of the maxim that everything is relative. The problem with the New Town is not that it's actually quite old, but rather that very few of its original buildings survive. As we shall see, however, that certainly doesn't mean that it is devoid of interest.

For purely practical reasons, given the nature of our itinerary the next day, we started off by familiarising ourselves with the walking route from the hotel to Prague's main railway station. On our way, we passed the Jerusalem Street synagogue, once called the Jubilee Synagogue in honour of the Austro-Hungarian emperor. Dating from the early 20th century, the building is a striking blend of Moorish and Art Nouveau architecture. Another surprise awaited us at the station, where the older part of the building turned out to be something of an attraction in its own right. Again dating from the 1900s, the former booking hall was another unexpected and beautifully restored art-nouveau treat.

|

|

LEFT: State Opera; new and old buildings of the National Museum; equestrian statue of St Wenceslas |

|

|

TOP RIGHT: Wenceslas Square BOTTOM RIGHT: People make their feelings known about events in Ukraine |

|

A short walk took us past the State Opera house to the two main buildings of the National Museum - and it was hard to imagine how a pair of buildings could possibly be more dissimilar. The first, placed cheek by jowl with the State Opera, was a stern, modern building in two distinct parts. Sitting firmly on the ground was a former stock exchange that had been extended in the 1960s by the construction of what was effectively a concrete upper deck, mounted on stilts. The extended building, never popular with locals, served as the Federal Assembly of Czechoslovakia until the dissolution of that country on 31 December 1992. Prior to the Velvet Revolution of 1989, the assembly's main function had been to rubber-stamp measures placed before it by the ruling Communist Party. The second building, more attractive in every way, was a grand neo-Renaissance structure dating from the 19th century, framing and dominating the upper end of Wenceslas Square. It was closed until at least 2016 for major renovations.

Wenceslas Square is recognised as the central attraction of the New Town. The funny thing is, though, that it isn't really a square at all, but rather a wide, tree-lined avenue - although comparisons with the Champs-Élysées are, in my opinion, over the top and unhelpful. If the National Museum frames its upper end, the role of focal point is taken by an equestrian statue of St Wenceslas. I found myself pondering another of life's little mysteries: how it could be that the name Václav was traditionally rendered as Wenceslas in English and had become widely known in this form thanks to a Christmas carol, yet such a translation was never deemed necessary or appropriate in the case of the much-admired former president, Václav Havel. Not that I'm complaining - the Czech form seems, if anything, more straightforward. In a touching indication of this trip's placement in time, the base of the statue had been turned into a makeshift shrine in a show of solidarity with the people of Ukraine.

Although our next main objective was Charles Square, we took a short diversion from the obvious route to visit the Antonín Dvořák Museum, on the off-chance that maybe it would depart from the norm and be open on a Monday. Dvořák is probably the most famous of Czech composers. Despite spending time in the USA and producing widely known works such as Symphony No 9 ('From the New World') and the American Quartet, he remained passionate about the traditional sounds of his homeland. A little known fact about him is that he was an avid railway enthusiast who was happy whiling away the hours at Prague's main station. Sure enough, the museum was closed on Mondays, but I was glad to have visited the spot where such a great musician is commemorated.

We met up with the Vltava once again at the start of the Jiráskův bridge - a spot that plays host to one of the city's most unusual buildings, the Dancing House (Tančící dům). Designed by Frank Gehry in partnership with a local architect, this building was formerly known as Fred and Ginger and indeed the corner section looks for all the world like a dancing couple.

|

|

LEFT: The Antonín Dvořák museum, Charles Square and the Dancing House |

|

|

|

|

RIGHT: A variety of New Town riverbank views, with the National Theatre undergoing restoration work |

|

|

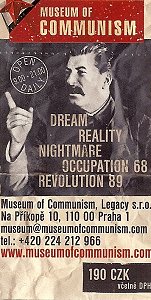

From there, we walked northwards along the right bank of the river, turned right at the National Theatre (which would have looked impressive were it not for the fact that it was undergoing extensive restoration work) and soon found ourselves at the opposite end of Wenceslas Square from the spot that we had visited earlier. From here, it was a short walk to the next item on the agenda, the Museum of Communism. This somewhat quirky venture aims to give a taste of the communist era in Czechoslovakia through the display of artefacts, statues, photographs, symbols and propaganda, all organised into three main sections based on the notions of dream, reality and nightmare. The museum's website cheekily claimed that "Lenin must be turning in his grave". Thankfully this was one museum that did open on Mondays. I found the experience informative and entertaining, occasionally sobering and sometimes amusing.

| Museum of Communism | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Old Town

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: Unexpected and delightful lunch stop | |

|

| ABOVE: A Segway tour pauses at the Estates Theatre |

In search of a suitable lunch spot, we crossed National Avenue (Národní třída) and in so doing, quietly slipped back into the Old Town. We passed the attractive Estates Theatre, where two of Mozart's operas were first performed. With so much understandable emphasis on celebrating local composers, it was easy to forget that Mozart loved visiting Prague to escape what he regarded as the stuffy atmosphere of the imperial court in Vienna.

We soon found our lunch stop in the unexpected shape of upscale sushi bar Made in Japan. It was good to be able to relax for an hour or so while enjoying beautifully presented and healthy food. It certainly wasn't a stereotypical choice and it was expensive by Prague standards, but we didn't grudge a penny. As Bruce pointed out, cheap sushi is not necessarily something to be welcomed!

|

LEFT: Return to Old Town Square |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ABOVE: The Old Town from the Town Hall tower | ||

Duly rested and fortified, we found ourselves in Old Town Square for the fifth time, within five minutes of leaving the restaurant. We caught the 3pm 'performance' of the Astronomical Clock before going up the Town Hall tower for a bird's eye view of our surroundings, both near and far. It was interesting to spot the places we'd visited earlier in the day and in so doing to retrace our route from this viewpoint; but for me, the most enduring images were those obtained by looking almost vertically downwards at the colourful buildings directly below.

With

the realisation that time was getting on, we quickly made our way to

our last sightseeing objective of the day, the subsection of the Old

Town known as Josefov, or the Jewish quarter. After

acquiring the necessary tickets, we managed to fit in rather hurried

visits to the Old Jewish Cemetery, the Pinkas Synagogue with its

moving 'wall of names' memorial to the 80,000 Bohemian and Moravian

victims of the Holocaust, the ornate Spanish Synagogue and the

curiously named Old-New Synagogue. I have no photos of this part of

the day due to a combination of restrictions and failing daylight.

With

the realisation that time was getting on, we quickly made our way to

our last sightseeing objective of the day, the subsection of the Old

Town known as Josefov, or the Jewish quarter. After

acquiring the necessary tickets, we managed to fit in rather hurried

visits to the Old Jewish Cemetery, the Pinkas Synagogue with its

moving 'wall of names' memorial to the 80,000 Bohemian and Moravian

victims of the Holocaust, the ornate Spanish Synagogue and the

curiously named Old-New Synagogue. I have no photos of this part of

the day due to a combination of restrictions and failing daylight.

After a well-earned rest back at base, we ended the day with the customary visit to the Executive Lounge, dinner at a local Vietnamese place - again, not exactly a Bohemian stereotype! - and a farewell-to-Prague nightcap in the Hilton's attractive lobby bar.